Dynamic programming is simple #4 (bitmap + optimal solution reconstruction)

- Dynamic Programming is Simple

- Dynamic programming is simple #2

- Dynamic programming is simple #3 (multi-root recursion)

- Dynamic programming is simple #4 (bitmap + optimal solution reconstruction) (this article)

After a long break, I finally found some time to return to this series of articles. There are still a couple of corner cases left to describe.

This time I will be talking about the case when the recursion arguments cannot be naturally cached. Also, you will learn not only how to find minimum/maximum but how to reconstruct the optimal solution as well.

Problem

There are quite a few problems requiring the method I am about to describe. I picked the one that, in addition to illustrating the technique, also requires doing one thing we have not done before: reconstruction of an optimal solution.

Short description of the task: we have a number of people, each of them has a certain set of skills, and we want to create a minimum possible team, so each skill is mastered by at least one person in the team.

Backtracking solution

The brute-force solution for this task is pretty straightforward. Each time we can make one of 2 decisions:

- Either we take the person in the team

- Or we leave this person behind

While making such decisions, we populate the set of skills our team has so far. It can be done recursively. While doing so, we count how many people we took to the team, and this way, we can find the minimum team size using this information. For now we just find the team size, we will find how to construct an actual team later.

Here is how the pseudocode might look (I have not tested it, just to illustrate the idea)

class Solution:

def smallestSufficientTeam(

self, req_skills: List[str], people: List[List[str]]

) -> List[int]:

all_skills = set(req_skills)

def backtrack(person: int, skills: Set[str]) -> int:

if skills == all_skills:

return 0

if person == len(people):

# Not enough skills accumulated, return

# large number to ignore the result

return len(people)

return min(

backtrack(person + 1, skills | set(people[person])) + 1, # Take this person in the team

backtrack(person + 1, skills), # Leave this person behind

)

min_team = backtrack(0, set())

As you see (if you read and understood my previous articles), this code looks very familiar with what DP usually looks like. The only problem: we cannot cache the function calls because the argument is mutable. I will show you an efficient way to address this issue in the next section.

Trick using bitmap

Suppose instead of set, we use immutable frozenset (which is hashable so that it can be a hash key). In that case, we can cache the values and access the cache to avoid visiting the same recursion branches multiple times.

class Solution:

def smallestSufficientTeam(

self, req_skills: List[str], people: List[List[str]]

) -> List[int]:

all_skills = frozenset(req_skills)

@lru_cache(None)

def dp(person: int, skills: FrozenSet[str]) -> int:

if skills == all_skills:

return 0

if person == len(people):

# Not enough skills accumulated, return

# large number to ignore the result

return len(people)

return min(

dp(person + 1, skills | frozenset(people[person])) + 1, # Take this person in the team

dp(person + 1, skills), # Leave this person behind

)

min_team = dp(0, frozenset())

Even though this is already a pretty good DP solution, it is usually worth going further and using bitmap instead of our frozenset.

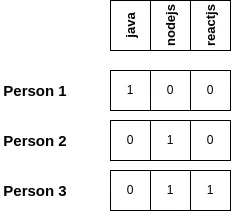

Let us assume we have three skills (java, nodejs, reactjs). We can represent skills for a person as an integer bitmap, where each skill will be represented as a bit set at a corresponding position. Also, notice the maximum number of skills we can have is 16, so even in the worst-case scenario, bitmap fits an integer effortlessly.

To understand the idea better, look at the picture:

Let us construct a mapping between a person and their skills represented as an integer.

# Construct a mapping from skill name to its index

skill_map = {skill: index for index, skill in enumerate(req_skills)}

# Initialise person's skills with int(0)

person_skills = [0] * len(people)

# Set skill bits for each person's integer

for person in range(len(people)):

skills = 0

for skill_name in people[person]:

skills |= 1 << skill_map[skill_name]

person_skills[person] = skills

Using this, we can rewrite our code using integers instead of sets.

class Solution:

def smallestSufficientTeam(

self, req_skills: List[str], people: List[List[str]]

) -> List[int]:

# All skills are represented as an integer, where len(req_skills) bits are set to 1

# Example:

# len(req_skills) = 3

# 1 << 3 = 01000

# 01000 - 1 = 00111

all_skills = (1 << (len(req_skills))) - 1

skill_map = {skill: index for index, skill in enumerate(req_skills)}

person_skills = [0] * len(people)

for person in range(len(people)):

skills = 0

for skill_name in people[person]:

skills |= 1 << skill_map[skill_name]

person_skills[person] = skills

@lru_cache(None)

def dp(person: int, skills: int) -> int:

if skills == all_skills:

return 0

if person == len(people):

# Not enough skills accumulated, return

# large number to ignore the result

return len(people)

return min(

dp(person + 1, skills | person_skills[person])

+ 1, # Take this person in the team

dp(person + 1, skills), # Leave this person behind

)

min_team = dp(0, 0)

Again, as you see, not much has changed, except that the skills variable is now an integer. You can also check a call graph, but I do not think it is necessary given that you have already read and understood my previous articles.

Take some time to understand the transition, and you will get the idea.

At this point, we already know the size of the minimum team, which is enough for most of the problems.

This trick of using a bitmap to store the binary information about the limited (< 64 items) set of data is widely used, and it is always nice to have it in your arsenal.

Reconstruction of an optimal solution

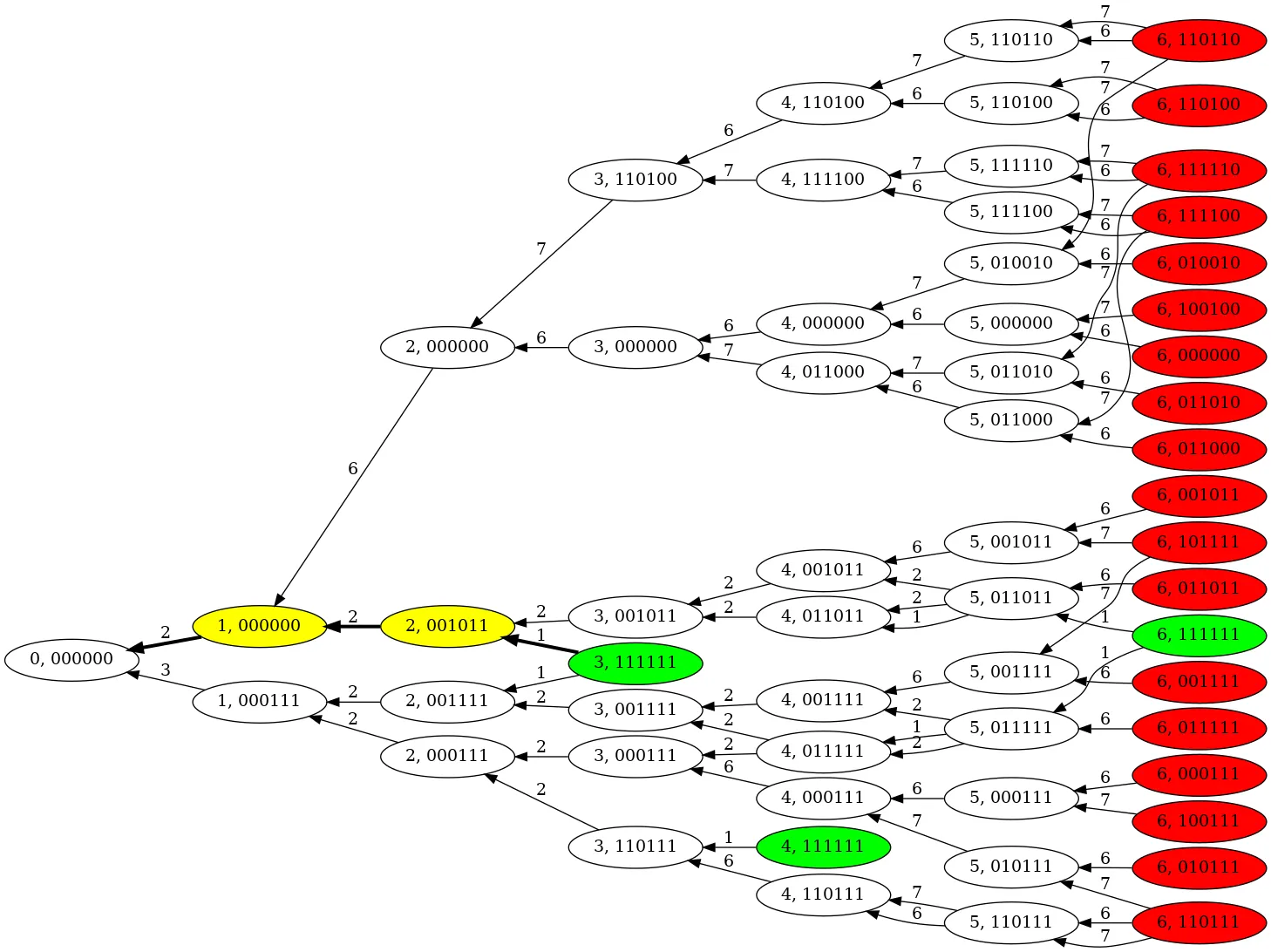

Let us look at the call graph of the following input data:

req_skills = ["algorithms", "math", "java", "reactjs", "csharp", "aws"]

people = [

["algorithms", "math", "java"],

["algorithms", "math", "reactjs"],

["java", "csharp", "aws"],

["reactjs", "csharp"],

["csharp", "math"],

["aws", "java"],

]

Here it is:

With the green colors here, we represent the leaf vertices, where we have all the required skills collected (i.e., all the skill bits are set to 1).

Red colors are for the leaf vertices, which are not a solution because some skills are missing.

Numbers over the arrows (edges) show us the minimum team size we can achieve via this path. Or you can think about that as the return values for the dp(person, skills) function.

Inside the node, you can see the call arguments (person number and accumulated skills bitmap so far).

Obviously, to reconstruct the path, we want to find the shortest path to one of those “green” nodes from the root.

To achieve that, we need just to try to follow the path which leads to the smallest sufficient team.

So remember, we already know the minimum size of the team we need, right? Actually, we already know two things:

- Minimum possible size of the team

- Pre-calculated and cached values of

dp(person, skills)function call

Using this information, we can traverse the call tree a second time, but this time we only need to follow the paths which lead us to the solution. This is literally what we do. We try to go all the paths from the current node and see if this path returns us the same minimum team size we already have (minus members we already picked along our way down the call tree). If it does, we follow this path in a greedy manner. In the end, we will reach a “green” node and stop here.

Here is the code doing that:

def reconstruct(

person: int, skills: int, min_team: int, path: List[int]

) -> None:

if person == len(people):

return

if dp(person + 1, skills | person_skills[person]) + 1 == min_team:

path.append(person)

reconstruct(

person + 1, skills | person_skills[person], min_team - 1, path

)

else:

reconstruct(person + 1, skills, min_team, path)

path: List[int] = []

reconstruct(0, 0, min_team, path)

Yellow nodes on the picture above are the ones that were added to an optimal solution.

There might be multiple solutions because multiple paths might lead to the same node, which is the case here. We can definitely find all of them if we want, but this is not the goal of this problem.

This method of path reconstruction applies to 100% of DP tasks. Basically, just traverse again and follow the path which leads to the optimal solution.

Worth mentioning that there are so many articles describing mystical ways to traverse some tables constructed using some kind of dark magic. While in reality, if you think about the task in terms of the mathematical induction and subproblems you want to solve, you just do what you would naturally do if you got a job to solve the same problem in the real world:

- Just try all the combinations and find the optimal one

- Knowing the optimal result, try all the combinations again and pick the one that fits it

PS: if you are looking for a complete solution, it is available here

Now you know

You know everything about DP. There is nothing more. All the DP problems are like this. No secrets left. This topic is completely demystified for you. Time to celebrate!

I was somewhat disappointed when I had learned what you just learned. After 50+ solved DP problems, I realized they are all the same. Before that, I thought solving DP problems is cool, only the best of the best can do that. Now I believe DP problems are the easiest ones you can get. Nothing to think about, no discoveries or A-ha moments, just follow the pattern.

But anyway, that applies to most things in our lives. It is the process of learning what is interesting, not the final result.

And before you slip into a depression and an existential crisis, I want to hold your attention a little more because I actually do have one more trick on my sleeve. I did not lie to you when I said you learned everything about the approach. That is true. But there is also one specific problem left, where it is actually difficult to do the most critical part of DP, namely “Decide what we have to do each step”. It is described in CLRS, and for that one, most people fail to find the correct recursive action since it is counter-intuitive. But we will talk about that next time.

Stay tuned!

This article is also available on Medium.